"Planet ISKCON" - 45 new articles

Vraja Kishor, JP: Astronomy and PrabhupadaIn his commentary on the Bhagavad Gita, Chapter 15, text 12 Srila Prabhupada makes the following rather shocking statement: “From this verse we can understand that the sun is illuminating the whole solar system. There are different universes and solar systems, and there are different suns, moons and planets also, but in each universe there is only one sun.” Is Prabhupada an astronomer? Yes, he is Jagad Guru, but is he an astronomer??? “Jagad Guru knows everything, including astronomy!” They protest. Does Jagad Guru know how to program in PHP? I am not trying to detract from the glory of Jagad Guru, but I desire to have an accurate conception of that glory. Jagad Guru himself sometimes answered similar challenges by saying, “I know that php is useless unless engaged in Krsna’s service, therefore I know the most important essence of PHP. That is how Jagad Guru ‘knows everything.’” I think we need to really embrace this sort of answer. So, is Prabhupada an astronomer? No. Is he Jagad Guru? Yes. Doesn’t he then know everything, including astronomy? Yes and no. He knows the essence of everything. This is different from knowing the details of astronomy. Now how about this – is there only one Sun in the universe? I highly doubt it. But Prabhupada said… Maybe Prabhupada was wrong. I am not saying maybe Prabhupada was wrong about anything that is significant to what Prabhupada is all about as the Jagad Guru of Krsna Bhakti! I am saying maybe he is wrong about a detail of astronomy. Lots of people balk at my attitude on this, in a big, big way. Maybe they are right and maybe I am a demon. But maybe I am just comfortable with the fact that Prabhupada is not a fantasy person. Personally I don’t mind if Prabhupada makes some syntax errors while programming a web-database interface in php and mysql. It doesn’t detract from his glory as Jagad Guru. Neither does him being wrong about something like a moon landing or how many stars are in a universe really bother me. At all. So, is Prabhupada wrong about this? Is there more than one sun in the universe? Here is one way that Prabhupada is wrong… First he says that there are different solar systems. Then he says that there is only one sun in the universe. What is a “solar system?” It is, by definition a number of planets orbiting a star, a sun. Therefore if there are many different solar systems, there are by definition many different suns. Here is one way that Prabhupada is right… Perhaps each “universe” only contains one solar system. If each solar system is a collection of bodies orbiting a Sun, and each “universe” consists of one solar system, then it is correct to say that there only one sun in each universe.This is the view that I personally accept. My view is that “universe” refers to the bodies collected around a star – the Sun. Thus each universe has one sun. Between each solar system is a huge span of interstellar space. It is my view that this is the three dimensional representation of the causal ocean of Sri Vishnu. In other words each solar system is a “bubble” in the vastness of the ocean of potentiality which is interstellar space. A galaxy is a clump of these bubbles – sort of like foam in the ocean. It is a greater “universe of universes.” There are thus many, many suns in what we call a galaxy. Between galaxies is an even more gigantic and unfathomable vastness of intergalactic space. I believe this is the pure karana-ocean separating clumps of solar-systems. What we call the “universe” in modern scientific vocabulary is what my personal understanding of the Vedic vocabulary would call a “universe of universes of universes.” • Email to a friend •  • •H.G. Sankarshan das Adhikari, USA: Monday 29 August 2011--Wet Cow Dung Laughs While Dry Dung Burns--and--Are there Five or 118 Basic Elements?A daily broadcast of the Ultimate Self Realization Course Monday 29 August 2011 The Supreme Personality of Godhead, Lord Sri Krishna, and His eternal consort, Srimati Radharani are enjoying transcendental pastimes in the topmost planet of the spiritual world, Sri Goloka Vrindavan. They are beckoning us to rejoin them. (Click on photo to see a larger image.) Our Mission: To help everyone awaken their original Krishna consciousness, which is eternal, full of knowledge and full of bliss. Such a global awakening will, in one stroke, solve all the problems of the world society bringing in a new era of unprecedented peace and prosperity for all. May that day, which the world so desperately needs, come very soon. We request you to participate in this mission by reviving your dormant Krishna consciousness and assisting us in spreading this science all over the world. Dedicated with love to ISKCON Founder-Acharya: His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, our beloved spiritual master, and to you, our dear readers. For Even More Nectar: Connect With Other Members of this Course. Join this Conference: http://groups.google.com/group/sda_students Today's Thought: Wet Cow Dung Laughs While Dry Dung Burns Uploaded from Bhaktivedanta Ashram, Austin, Texas USA The proud, successful materialist laughs to see how much better off he is than those who are suffering in destitute impoverished conditions. But he does not realize that his successful position is only temporary. He is briefly enjoying the result of his previous pious activities while engaging in all sinful nonsense. He does not realize that as soon as his pious karma is exhausted he will be dragged down by the stringent laws of nature into a pitiable condition. In this connection there a Bengali proverb as follows: ghute pore gobar hase When the dry cow dung is burning in the fire, the wet cow dung laughs. The materialistic person is laughing like wet cow dung. He does not realize that soon he will be dry and he will be tossed into the fire. Sankarshan Das Adhikari Dry Cow Dung Goes into the Fire http://www.backtohome.com/images/drydungintofire.jpg Answers by Citing the Vedic Version: Question: Are there Five or 118 Basic Elements? Could you please highlight the relationship between the five material elements described in the Bhagavad-gita and the 118 elements listed in the chemistry periodic table? Chandra Answer: 118 Elements Composed of the 5 Elements The 118 elements mentioned in the periodic table of modern day chemistry can be further sub-divided into the five basic elements described in the Bhagavad-gita: earth, water, air, fire, and ether. Material science has not yet discovered this, but those who are followers of Vedic science already know this. Sankarshan Das Adhikari Transcendental Resources: Receive the Special Blessings of Krishna Now you too can render the greatest service to the suffering humanity and attract the all-auspicious blessings of Lord Sri Krishna upon yourself and your family by assisting our mission. Lectures and Kirtans in Audio and Video: Link to High Definition Videos Link to Over 1,000 Lecture Audios Lecture-Travel Schedule for 2011 http://www.ultimateselfrealization.com/schedule Have Questions or Need Further Guidance? Check out the resources at: http://www.ultimateselfrealization.com or write Sankarshan Das Adhikari at: sda@backtohome.com Get your copy today of the world's greatest self-realization guide book, Bhagavad-gita As It Is available at:http://www.ultimateselfrealization.com/store Know someone who could benefit from this? Forward it to them. Searchable archives of all of course material: http://www.sda-archives.com Receive Thought for the Day as an RSS feed: http://www.backtohome.com/rss.htm Unsubscribe or change your email address Follow us on Twitter: http://twitter.com/Daily_Thought Thought for the Day on Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/Ultimate.Self.Realization Copyright 2005-2011 by Ultimate Self Realization.Com Distribution of this material is encouraged. Simply we request you to acknowledge where it is coming from with a link to our sign up page: http://www.backtohome.com Our records indicate that at requested to be enrolled to receive e-mails from the Ultimate Self Realization Course at: This request was made on: From the following IP address: • Email to a friend •  • •Manoj, Melbourne, AU: 226. Seeing Him

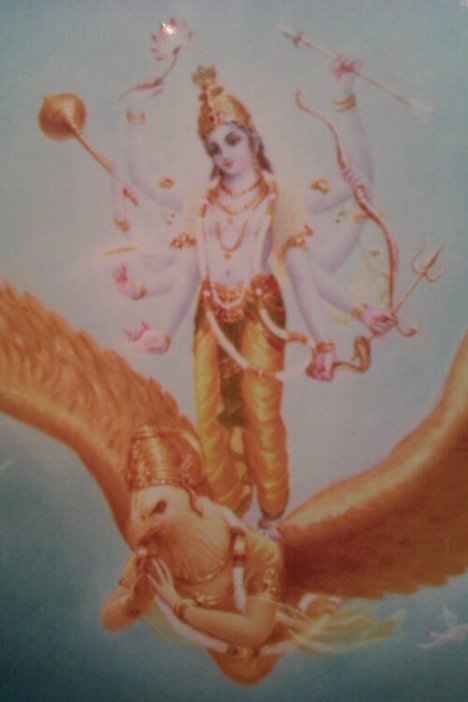

I was at Crossways restaurant today for lunch. As I sat there by myself, a father and his 20 year old son decided to share the table with me. For the next one hour, we spoke about Hare Krishna in Australia, the philosophy in simple language, lack of quality leaders in the world, the rise of food prices, vegetarian cooking etc etc. All I wanted to achive was that they would someday see the form of the Lord at the temple. Towards the end, the son said he would surely drop by the temple on weekends. It was a great lunch. And during our talk, this picture on the wall of the Lord overlooked us. So beautiful…. • Email to a friend •  • •ISKCON Melbourne, AU: Daily Darshan

• Email to a friend •  • •ISKCON Melbourne, AU: Daily Class - Yamuna Lila MatajiSrimad Bhagavatam 1.2.6 - As pouring water on the root of a tree energizes the trunk, branches, twigs and everything else, simply worshiping Krsna automatically satisfies the demigods (yatha taror mula-nisecanena...). • Email to a friend •  • •Kurma dasa, AU: Festive FareI catered for my Dad's 87th birthday party last weekend. Here's some highlights of the spread.

Inari-zushi are one of my favourite ways of serving sushi rice, and I have had loads of practice at making them. They are served here on a bed of watercress leaves. Splendid finger food!

I had a bash at cake decoration - it has never been my specialty. I need a bit more practice with the piping bag. The mini-cupcakes were based on a great recipe for eggless cupcakes by fellow food blogger Sanjana.

The citrus cheesecake was based on a recipe in my very first cookbook. Lime, and orange flavoured inside with a mandarin jelly topping and glace orange segments dipped in something brown and naughty.

Here's those mini-cupcakes again - pretty little dudes. It was great fun putting them together, and I gave myself plenty of time for a meditative and careful construct.

And even closer encounters of the cupcake variety. Two varieties of cupcakes and two varieties of buttercream toppings plus eight different toppings meant that almost no two cupcakes were exactly the same. Simultaneously one and different! • Email to a friend •  • •Japa Group: Hankering For Pure Chanting

Our main objective is to achieve pure love for Krsna and through our Spiritual Master's mercy and also Srila Prabhupada's blessings we can be able to move forward in our spiritual path. Here is a beautiful very describing Lord Nityananda's pastimes which brings us faith in the chanting of the holy names. "I perpetually worship Sri Nityananda, the root of the tree of krishna-bhakti, who wandering around in Bengal approached the door of every home. With upraised arms he exclaimed: " O Brothers! Please constantly chant the holy names of Hari. If you do so, I will take the responsibility to deliver you from the ocean of material existence." Sri Nityanandastakam by Srila Vrindavana Das Thakura I wish you a very blessed week of chanting. your servant, Aruna devi • Email to a friend •  • •Manoj, Melbourne, AU: 225. The Soul Poster

I am at the dentist for regular checkups and I noticed this poster at the reception table. What a good idea ! Basically around the poster, titles of various problems or symptoms related to loneliness are indicated and for each one of them, there is a verse from the bible giving a solution to that problem. And they have a symptom per alphabet listed. And I thought, why can’t the Hare Krishnas have something similar too with a break down of human miseries around a poster and a corresponding verse from Bhagavatam or Bhagavat Gita as solution? It could be a great gift item to temple visitors or something that can be stuck at work. Just an idea to get us noticed and to engage the audience. What do you think? • Email to a friend •  • •Manoj, Melbourne, AU: 224. Sunday Out and aboutGood morning ! That’s what it was in Melbourne yesterday. Beautiful well lit and warm morning for a good part of the day. Birds, humans and devotees all looked happy as the sun shone on us. Nrsimha Kavaca Prabhu presented a great and enliveling bhagavatam class explaining why bhagavatam is such an important literature for all us. I enjoyed one of the examples he took. He said that United Nations is doing nothing to establish real peace on earth. All that its doing is increase the number of flags outside its big office. After a shortwhile, I took a 2 hour ride into regional Victoria to a place called Bendigo. We had a strong home program there. Over the last 1 year we have been trying to develop a base there. And so far its been going well. The 4 hour ride in total was very pleasant and informative with my guest speaker Jagannath Ram Prabhu educating me on so many spiritual matters. So many things that got me thinking. More on those later. Then got to the temple by 6pm and ran straight up to the Prasadam hall ! You know what happens there. That was my Sunday. Talk to you soon ! • Email to a friend •  • •Bharatavarsa.net: Bhakti Vikasa Swami: False love and actual loveOutside of loving God there is no possibility of loving. Rather, there is lusty desire only. Within this atmosphere of matter, the entire range of human activities -- and not only every activity of human beings but all living entities -- is based upon, given impetus and thus polluted by sex desire, the attraction between male and female. For that sex life, the whole universe is spinning around -- and suffering! That is the harsh truth. So-called love here means that "you gratify my senses, I'll gratify your senses," and as soon as that gratification stops, immediately there is divorce, separation, quarrel, and hatred. So many things are going on under this false conception of love. Actual love means love of God, Krsna. >>> Ref. VedaBase => SSR 7d: Protecting Oneself from Illusion • Email to a friend •  • •Mukunda Charan das, SA: Aham Bija-pradah Pita‘The living entities are combinations of the material nature and the spiritual nature. Such living entities are seen not only on this planet but on every planet, even on the highest, where Brahma is situated. Everywhere there are living entities; within the earth there are living entities, even within water and within fire. All these appearances are due to the mother, material nature, and Krsna’s seed-giving process. The purport is that the material world is impregnated with living entities, who came out in various forms at the time of creation according to their past deeds’ – A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, Bhagavad-gita As It Is 14.4 Purport Filed under: A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, General, Realizations Tagged: A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, aham bija-pradah pita, aries, bhagavad gita comment, bhagavad-gita as it is, postaweek2011, spiritual and material • Email to a friend •  • •Bhakta Chris, New York, USA: The Bhagavad Gita And The Value of Vulnerability

Incidentally, during my very first banking interview, my interviewer handed me a sheet of paper, which stated, "Investment Banking is a business where thieves and pimps run freely on the corridors and the few good men die the death of a dog!" In big, bold letters at the bottom it said, "THERE IS ALSO A NEGATIVE SIDE!" With a stern look, my interviewer asked me my first interview question, "Which one of the three are you?" The message was written on the wall. I was walking into an environment where failure, weakness and honesty were treated as disease. The gravity of the challenge only became evident in the very first week of my new profession after I landed one of the offers Shannon had set up for me. The intensity of success-orientation, the sense of image consciousness, and the drive to be the best filled every nook and corner at work. In that environment where every junior associate's performance is closely monitored and quickly labeled, I had my first major stumble. I was the only one in my class of 74 associates to fail my first major financial services examination -- the Series 7. As I walked out of 100 Williams Street that evening, it was a sinking feeling. I waited until all my classmates had walked out -- not wanting to be with any of them. A deep sense of personal failure and the fear of being labeled as incompetent clouded my mind. I was extremely worried about losing the positive regard of my colleagues right at the start of new career. I was thinking to myself, "I will just say I passed! No one will know anyways!" Determined to save my face at all cost and rationalizing it very well, I made the decision to "cook the books". That evening, I spent time alone looking inside myself in a way that I never did before. There was an extreme uneasiness to sit and watch my feelings. For the first time, I encountered the fact that in my headlong rush to achieve, I had become a master at repression and a compulsive achievement machine. I had so long invested in an image that I carefully preserved to convince others and myself about my capabilities. Behind an armor of achievements, I experienced the pain of my own vulnerability. I realized that I lived in a culture that discouraged vulnerability. Vulnerability is usually associated with weakness -- something that I could be rejected or exploited for. In this culture, I have grossly and subtly ingested the notion that I should not have any weakness -- so much so that when I came in touch with my natural human limitations, it was painfully embarrassing. My idealized self-image was fractured. I realized that in the pursuit to keep the image alive I had invested in an image to gain positive acceptance from others. As I entered the office the next morning, an excited bunch of associates and analysts were talking about the exam just next to my cubicle. One of the analysts, Matt Fiorello, asked, "How did it go, Ram?" I gathered all my courage and said that I failed. There was silence and I felt the pain run through every pore of my body. Nobody knew what to say. A few consolations floated and the crowd dispersed. As I sat on my seat, I experienced a state of true grounding -- as if I had let go of a huge load. There was acceptance of my own vulnerability and a simple, lighthearted joy in that acceptance -- a relief that I did not have to live with an image. Later that evening, Matt stopped by my desk. "I cannot believe you spoke the truth so easily", he said. "No excuses. I feel very inspired. Thank you for being so trustworthy". I was pleasantly surprised and grateful. That evening, I experienced a deep sense of freedom. I realized how I had unconsciously become a prisoner of my own image. I realized that true personal development needs an honest and compassionate acknowledgment of our human limitations and a proper space to socialize them. We need to accept ourselves before others can accept us as we are. That acknowledgment can prove to be an invaluable guardian against the self-deception mechanisms of the ego. Otherwise, we become desensitized to our authentic self and begin to package ourselves simply to attract favorable attention. "How do I come across?" becomes the name of the game. Even amongst "friends", it becomes difficult to take off the mask due to the fear of rejection. The slick, smooth surface conceals the emotional neediness to be accepted as we are. In such a stifling environment, true personal development does not happen. We remain slaves of an image without grounding in who we truly are. This very lesson is conveyed at the onset of the Bhagavad Gita, India's classic on yoga and spiritual wisdom, where prince Arjuna provides a remarkable example of vulnerability. Arjuna was a veteran of many battles and had never lost a single combat. His acts of prowess, courage and intelligence were world-famous. Yet, Arjuna faced a situation where he had to fight his own kinsmen. His courage was tested and he broke down in front of his dear friend Krishna, expressing his distraught situation. In a matter of moments, Arjuna turned from a mighty warrior into a weakling, right in front of his opponents. In that exhibition of weakness, Arjuna exhibited great courage. It is that honest expression of weakness that set the stage for timeless wisdom to be spoken. Consequently, he received the strength and inspiration to confront his inner doubts and overcome them. The same can happen in our lives if we take the courage to be vulnerable; when we learn to walk through the door of fear that has kept us prisoners to our idealized self-image. We can wake up to our authentic potential and experience the sense of freedom. It can also help us better understand and be compassionate to another's needs.• Email to a friend •  • •Akrura das, Gita Coaching: NEW VIDEO: BHAGAVAD GITA SUCCESS PRINCIPLES PART 5• Email to a friend •  • •Akrura das, Gita Coaching: NEW VIDEO: BHAGAVAD GITA SUCCESS PRINCIPLES PART 4• Email to a friend •  • •Akrura das, Gita Coaching: NEW VIDEO: BHAGAVAD GITA SUCCESS PRINCIPLES PART 3• Email to a friend •  • •Akrura das, Gita Coaching: NEW VIDEO: BHAGAVAD GITA SUCCESS PRINCIPLES PART 2• Email to a friend •  • •Akrura das, Gita Coaching: NEW VIDEO: BHAGAVAD GITA SUCCESS PRINCIPLES PART 1• Email to a friend •  • •Akrura das, Gita Coaching: JANMASTAMI LECTURE IN HARRISBURG• Email to a friend •  • •Akrura das, Gita Coaching: THE COMPETITION OF HAPPINESSSo transcendental pleasure mean feeling of pleasure through Krsna. Just like the gopis and Krsna. Gopis, when they saw Krsna is pleased, they became happy, and Krsna, when He saw that the gopis are happy, He become happier. Again the gopis see that Krsna is happier, they, again they become more happy. In this way, there is competition of happiness. The gopis see Krsna happier; they feel happiness, and Krsna sees gopis happier; Krsna feels happiness. This word is described in the Caitanya-caritamrta: dui lagi hura huri. This is spiritual competition. So: "Pure devotional service automatically puts one in transcendental pleasure." In the material pleasure, if I see you happy, I am unhappy; If I see you unhappy, I become happy. This is nature. I may say otherwise, but material nature is, if one is put into difficulty, then I become very happy, and if I am happy, others become envious. This is material pleasure. Whereas spiritual pleasure means that when one sees Krsna is happy, a devotee's happy, the other devotee becomes happier. That is spiritual pleasure. In the spiritual world there is competition, but when one is advanced, the competitor become happy: "Oh, he's so advanced. I could not do so." There is no enviousness. In the material world, if one is advanced, other, who is not advanced, he's envious. This is the difference between spiritual pleasure and material pleasure. It is not difficult to understand. Material pleasure means if you are happy, I become unhappy; if you are unhappy, then I become happy. This is material pleasure. And spiritual pleasure means by seeing your happiness, I become happy. By seeing... But there is no distress in the spiritual world. Simply by seeing the happiness of other devotee, another devotee becomes happier. - Srila Prabhupada, Lecture of the The Nectar of Devotion - Vrndavana, November 3, 1972 • Email to a friend •  • •Madhava Ghosh dasa, New Vrndavan, USA: Bhakta Tirtha Swami On ForgivenessFrom Reflections May 2010 Question: You described a lack of forgiveness as one of the symptoms of anger. When someone hurts us, it can lead to feelings of anger and an inability to forgive. Forgiveness seems easier to apply if the other person changes their behavior and possibly acknowledges their hurtful behavior. However, such a change may not happen immediately so how do we relinquish anger and forgive a person who may even continue to repeatedly hurt us in the present without feelings of remorse? B.T.Swami: Forgiveness does not mean that we turn ourselves into a punching bag so that others can continuously throw blows at us, nor does it mean that we become a doormat for others to walk over and wipe their feet. People should certainly remove themselves from a position in which they function as the target of another's attacks. Forgiveness does not mean the following: • We feel that the person or people who hurt us should be allowed to continue. Forgiveness does mean the following: • We are not going to allow the person who hurt us to continue hurting us by constantly holding onto them or their actions. The more we hold onto the anger associated with the event, the more we allow the person to repeatedly assault us. In other words, forgiveness is something we mainly do for ourselves so that we can personally free ourselves from various stagnations because such stagnations can affect us physically, psychologically as well as spiritually. If another person chooses to be continuously obnoxious, we do not want to allow their nonsense to impose itself upon us in any way. We want to be fully free to act in the spirit of love in spite of the environment or the person's actions. The spirit of love entails knowing what is actually best for us as well as knowing what is best for the other person's spiritual well-being. When we hold unhealthy anger, it normally means that we want to retaliate or we want to see the person hurt. Consequently, we must ask ourselves, "How much harm or pain must the person experience before we can release them from our psyche?" Their feelings of remorse or lack of remorse should not really dictate or impose upon our own life. Filed under: News, Ramblings or Whatever • Email to a friend •  • •Srila Prabhupada's Letters1969 August 28: "At present my activities are from Hamburg to Tokyo, a distance of 14,000 miles. The circumference of the earth is 25,000 miles. So this should be covered by some of our Godbrothers. There is immense potency of preaching the philosophy of Krishna Consciousness and I wish that all my Godbrothers should preach this sublime message everywhere." • Email to a friend •  • •Srila Prabhupada's Letters1968 August 28: "The decision is now complete and I am going to New York to arrange for the press opening. I wish to meet Satyavrata; if he does not like to come to our temple, then I wish to go there to his place. Please arrange for this on Sunday." • Email to a friend •  • •Srila Prabhupada's Letters1968 August 28: "Service to Laksmi-Narayana, and Radha Krishna, it requires highly elevated position. To worship the Lord in the Form of Jagannatha is more congenial. Jagannatha is especially favorable to those who are not strictly advanced to the Brahminical culture. He accepts service even from those who are fish-eaters." • Email to a friend •  • •Akrura das, Gita Coaching: GITA COACHING COURSE IN CHICAGOThese devotees seem eager to help devotees succeed. We had a 6-hour course with 30-40 devotees attending, including several youngsters and children. Here is an excerpt from the Gita Coaching Course Handbook: Lesson 2: The Qualities of a Coach 1. A Genuine Desire To Help Others SucceedEvery coachee, by contacting a coach, demonstrates a need to solve a problem or achieve a result. The coach must have the desire and the ability to help the coachee succeed. If you don't develop this attitude, you will not provide a proper service for your coachees. 2. Genuine Interest In OthersA coach must be able to focus exclusively on the coachee. A tendency to think about yourself will encourage you to compare coachee's situation with your own. Focus on the coachee will allow you to empathise with him and show genuine interest in his life. 3. A Greater Interest In People Than In ThingsA coach who is more interested in things than people will be motivated by material gain. This may incur risk of putting your needs above the needs of the coachee – which is unacceptable. 4. The Ability To Balance Your Own Life And To Put Your Own Issues On HoldA coach with imbalance and stress in his life is unlikely to deliver successful coaching. His personal issues will deflect attention from focus on the coachee's issues. To coach effectively, you must come to each session with a clear mind. 5. Totally Committed To Coachee's successDid you ever have a teacher, a leader, a friend, a coach, or an adviser who believed in you when you didn't believe in yourself? One who stayed with you regardless. Not someone who was too soft and permissive with you, someone who gave in to you, but someone who would neither give in to you nor give up on you. 6. Excellent Verbal Communicator"Most important is how the man in Krsna consciousness speaks, for speech is the most important quality of any man." Bg 2.54 P "… speaking words that are truthful, pleasing, beneficial, and not agitating to others, and … regularly reciting Vedic literature." Bg 17.15 The entire coaching process is based on verbal communication. Research has shown that over 70% of normal communication relies on body language (posture and facial expression) for its effectiveness. In telephone coaching this element is removed so what is said and how it is said is of a greater importance. To be a life coach, you must develop the ability to say what you mean without any ambiguity, to mean what you say with absolute confidence, and the tenacity to repeat a point as often as necessary to ensure it's clear. Verbal communication is a two-way activity that involves listening as well as speaking. During coaching sessions, allow your coachee to speak for a minimum of three quarters of the time while you listen attentively. If your peers, family and friends invariably understand what you are saying in normal conversations, you already have a good grounding in verbal communication skills. If you are frequently misunderstood, or if they have a tendency to talk over you, then you need to develop abilities in this area. Your coachees might expect you to provide an excellent service and one way they will judge you is by the language you use. Avoid using jargon, familiar or trendy language as this may negatively affect your relationship. 7. Confidential "… revealing one's mind in confidence, inquiring confidentially, …" - Nectar of Instruction 4 Anything can be discussed in a coaching session. Your coachees must gain absolute trust in your confidentiality if they are to tell you about their personal life and the issues that concern them. Only if they have trust in your confidentiality will they be willing to provide you with the detailed information you may need to help them achieve their goals. If at any time you are unsure about whether to reveal any information about a coachee – don't! Think how you would feel if your confidential information was being passed to others. Never assume that the coachee won't mind. This means, for example, that you never mention coachees' names to any third party without their consent and that you keep any notes about coaching sessions securely. If you keep them on a computer, ensure they are password protected. It's important that what you say to the coachee and what you do with that coachee match. For example, it is no good to say that you observe complete confidentiality in coaching sessions and then use examples of other coachees in the session. Your actions must match your words. 8. Neither Judgemental Nor Critical"… whose heart is completely devoid of the propensity to criticize others." - Nectar of Instruction 5 Coaching is about where your coachees are now and where they want to be in the future. Consider that their perception of their current situation may be totally different from yours. As a coach it is your service to encourage and motivate your coachees to take the action that will move them forward, from where they are to where they want to be. To undertake this role you must not be judgmental or critical, as these traits will limit your coachees rather than empowering them. Your role includes helping them evaluate the steps they are taking and the progress they are making, but you will not judge or criticize them. Always respect your coachee's free will. Don't try to impose anything on them or control them. 9. Explorer And Provider Of Options "For a devotee of the Supreme Personality of Godhead, everything is possible …" SB 5.1.35 P As a life coach you are a catalyst or facilitator. Part of your role is to help coachee think for himself and find his own solutions, sometimes with the help of others. Another part of your role is to be able to discover a variety of possible options to your coachees. Your service is to, together with the coachee, discover all the available options, those suggested by the coachee, by others, by yourself and including ones that the coachee may be avoiding. Some of these might come from your insight into their situation, gained because you are removed from their everyday concerns, worries or fears which may be limiting their vision. Next, you encourage the coachee to select for himself, from the options, the one or more that will move him forward. By letting the coachee select the option, you are giving him the added incentive that comes from having chosen this route for himself. You are there to help your coachees to do things, not to do those things for them, and to expand their horizons and facilitate the empowerment that comes from the freedom of choice and a higher connection. 10. Committed"I have got always time to answer the letters of sincere souls because my life is dedicated for their service." - Srila Prabhupada, Letter to Christopher, Montreal 13 July 1968 One of the favourite coaching principles is, "If you continue doing what you are doing, you will continue getting what you are getting". This means that a coachee, who is in a situation that no longer serves his goals, must change something in order to change the results. Your commitment to encouraging such change is paramount to the success of your coaching. You will encourage your coachee to define the actions that will move him forward and then to take those actions. You will seek your coachee's commitment to take the necessary action and you will be committed to ensure, with friendly firmness and positive encouragement, that he does take such actions. • Email to a friend •  • •New Vrndavan, USA: Tuesday, August 30 @ noon – Mandatory Istagosthi

Dear Brijabasis, Please accept my humble obeisances. All glories to Srila Prabhupada. There is a mandatory Istagosthi for all devotees serving and living at the temple and its departments. This includes, but is not limited to, the following facilities: (1) Radha-VrindabanChandras’ Temple, (2) Govinda’s Snack Bar, (3) Palace Lodge, and (4) Prabhupada’s Palace of Gold. Any and all community members are welcome to participate. Thank you. Hare Krishna! DATE: Tuesday, August 30 TIME: 12:00 noon – 1:30 PM LOCATION: Prasadam Hall

• Email to a friend •  • •Srila Prabhupada's Letters1970 August 28: "If you all continue to follow the rigid schedule with vow, going on Sankirtana and studying our literatures, it is sure and certain to increase your spiritual power to attract more and more sincere persons to Krsna Consciousness." • Email to a friend •  • •Srila Prabhupada's Letters1972 August 28: "My special blessings for those who are doing so much for our Lord. They must be specifically blessed to go back home, back to Godhead without any delay for waiting for the next life. Thank them very much on my behalf." • Email to a friend •  • •Srila Prabhupada's Letters1973 August 28: "If you can arrange for meetings with Professor Dimock and other professors then do it and I shall come. Krishna is very kind upon you. He has given you so many responsible tasks. Bhaktivinode Thakura used to say all difficult tasks he had to execute for Krishna were considered as great pleasure for him." • Email to a friend •  • •Srila Prabhupada's Letters1973 August 28: "Regarding the criticism from others, that may be there but we have to follow our own principles. If we maintain these principles rigidly there is no question of fall down and without any difficulty our progressive march will advance." • Email to a friend •  • •Australian News: Kids Janmashtami Part TwoSee the Kids who won the colouring-in competition, see the demon from hell attack Krishna, see the kids punch the demon in the head. See the demon chewing on children. Ok that didn’t happen but it was a lot of fun anyway.

Generated by Facebook Photo Fetcher            • Email to a friend •  • •Srila Prabhupada's Letters1975 August 28: "If you can't sell the land then you can lease to us for 99 years. The land is lying vacant from a long time 50 years. Now if it can be utilized for the benefit of the Institute why there should be objection." • Email to a friend •  • •H.H. Sivarama SwamiA material desire is explained as a desire to enjoy the material world to its fullest extent. In modern language, this is called economic development. - Srila Prabhupada • Email to a friend •  • •Toronto Sankirtan Team, CA: Penny Power

• Email to a friend •  • •Toronto Sankirtan Team, CA: The power of the Maha Mantra... on paper!

• Email to a friend •  • •Mayapur Online: Memorial to be built for Jayananda PrabhuISKCON's Governing Body Commission has accepted a proposal from Vishoka Dasa of New Vrindaban, West Virginia, and Krishna-Mangala Dasa of Russia that they establish a memorial for Jayananda Prabhu—considered a modern-day saint by members of ISKCON—although he passed away as far back as 1977. • Email to a friend •  • •Sutapa das, BV Manor, UK: Soul Mates

• Email to a friend •  • •ISKCON Melbourne, AU: Daily DarshanThe Lord, who is supreme and is the oldest of all, is unlimitedly merciful. I wish that He may smilingly bestow His benediction upon me by opening His lotus eyes. He can uplift the entire cosmic creation and remove our dejection by kindly speaking His directions. SB 3.9.25.

Oh unlimitedly merciful Lord, please give me the strength to follow your instructions.

Here is today's darshan. • Email to a friend •  • •H.H. Sivarama SwamiWe are only ordinary men, playthings of fate. Indeed, whether a person acts on his own or is forced by others, he is always under the Supreme Lord’s control. - Vasudeva • Email to a friend •  • •Japa Group: Meaning Of The Sixteen Names PT.10Rama govardhana-dari-kunje parirambha-vicaksanah sri radham ramayamasa ramastena mato harih Krsna, who is expert at embracing, sports with Radha in the forest groves or in the caves of Govardhana. Thus He is known as Rama. Jiva Goswami • Email to a friend •  • •H.H. Sivarama Swami: Sadhaka dasa wonders, among other things, how to communicate to his guru – also his managing authority – when the latter is not a good manager

• Email to a friend •  • •Yoga of Ecology, Bhakta Chris, USA: At Vacant Homes, Foraging For FruitBy KIM SEVERSON from the New York Times |

Unsubscribe from all current and future newsletters powered by FeedBlitz

| Your requested content delivery powered by FeedBlitz, LLC, 9 Thoreau Way, Sudbury, MA 01776, USA. +1.978.776.9498 |

TABLA - FUENTES - FONTS

SOUV2

- SOUV2P.TTF - 57 KB

- SOUV2I.TTF - 59 KB

- SOUV2B.TTF - 56 KB

- SOUV2T.TTF - 56 KB

- bai_____.ttf - 46 KB

- babi____.ttf - 47 KB

- bab_____.ttf - 45 KB

- balaram_.ttf - 45 KB

- SCAGRG__.TTF - 73 KB

- SCAGI__.TTF - 71 KB

- SCAGB__.TTF - 68 KB

- inbenr11.ttf - 64 KB

- inbeno11.ttf - 12 KB

- inbeni11.ttf - 12 KB

- inbenb11.ttf - 66 KB

- indevr20.ttf - 53 KB

- Greek font: BibliaLS Normal

- Greek font: BibliaLS Bold

- Greek font: BibliaLS Bold Italic

- Greek font: BibliaLS Italic

- Hebrew font: Ezra SIL

- Hebrew font: Ezra SIL SR

Disculpen las Molestias

Planet ISKCON - 2010 · Planet ISKCON - 2011

Conceptos Hinduistas (1428)SC

Aa-Anc · Aga - Ahy · Ai - Akshay · Akshe - Amshum · Ana - Ancie · Ang - Asvayu · Ata - Az · Baa-Baz · Be-Bhak · Bhal-Bu · C · Daa-Daz · De · Dha-Dry · Du-Dy · E · F · Gaa-Gayu · Ge-Gy · Ha-He · Hi-Hy · I · J · K · Ka - Kam · Kan - Khatu · Ki - Ko · Kr - Ku · L · M · N · O · P · R · S · Saa-San · Sap-Shy · Si-Sy · Ta - Te · U · V · Ve-Vy · Y · Z

Conceptos Hinduistas (2919)SK

Aa-Ag · Ah-Am · Ana-Anc · And-Anu · Ap-Ar · As-Ax · Ay-Az · Baa-Baq · Bar-Baz · Be-Bhak · Bhal-Bhy · Bo-Bu · Bra · Brh-Bry · Bu-Bz · Caa-Caq · Car-Cay · Ce-Cha · Che-Chi · Cho-Chu · Ci-Cn · Co-Cy · Daa-Dan · Dar-Day · De · Dha-Dny · Do-Dy · Ea-Eo · Ep-Ez · Faa-Fy · Gaa-Gaq · Gar-Gaz · Ge-Gn · Go · Gra-Gy · Haa-Haq · Har-Haz · He-Hindk · Hindu-Histo · Ho-Hy · Ia-Iq · Ir-Is · It-Iy · Jaa-Jaq · Jar-Jay · Je-Jn · Jo-Jy · Kaa-Kaq · Kar-Kaz · Ke-Kh · Ko · Kr · Ku - Kz · Laa-Laq · Lar-Lay · Le-Ln · Lo-Ly · Maa-Mag · Mah · Mai-Maj · Mak-Maq · Mar-Maz · Mb-Mn · Mo-Mz · Naa-Naq · Nar-Naz · Nb-Nn · No-Nz · Oa-Oz · Paa-Paq · Par-Paz · Pe-Ph · Po-Py · Raa-Raq · Rar-Raz · Re-Rn · Ro-Ry · Saa-Sam · San-Sar · Sas-Sg · Sha-Shy · Sia-Sil · Sim-Sn · So - Sq · Sr - St · Su-Sz · Taa-Taq · Tar-Tay · Te-Tn · To-Ty · Ua-Uq · Ur-Us · Vaa-Vaq · Var-Vaz · Ve · Vi-Vn · Vo-Vy · Waa-Wi · Wo-Wy · Yaa-Yav · Ye-Yiy · Yo-Yu · Zaa-Zy